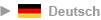

Talking and fighting

A dialogue between someone who teaches fighting and someone who writes about it, about a well-known analogy which is still often used by WT teachers: you learn WT as you learn a foreign language.

|

During a short stroll by the beach on the way back to the hotel from the first seminar of the year in Tenerife, my conversation with SiFu turned to a question he had been asked while teaching.

Many WT people are familiar with the comparison between learning a language and learning WT which SiFu made in his reference work "On Single Combat". In rough terms this says that the SiuNimTau corresponds to the alphabet and the ChamKiu to individual words, that ChiSao is comparable to grammar and that LatSao is something like a simple conversation.

The student's question to SiFu was this: "How does this analogy fit into Inner WingTsun?". After pausing for thought, SiFu answered that if one wanted to use the same comparison, practicing the solo and partner forms would be akin to learning the grammar, while Inner WingTsun gives us the syntax.

I meant that the additional solo and partner exercises correspond to the "grammar" and its conjugation and declination exercises. However, I also consider the classic forms – SiuNimTau and ChamKiu – to be grammar subject to grammatical rules. Thinking back to my old linguistic studies, I remember that we use the term "syntax" for the construction of sentences with main and subordinate clauses. I did not want to distinguish between outer and Inner WT.

During our walk, SiFu returned to the comparison by considering whether in linguistics, the syntax is not actually part of the grammar.

I seem to remember that this was actually your idea. But I can imagine that syntax could well be seen as part of the "grammar".

And if this is taken into account, think of the effects this would have on the analogy between learning a language and WingTsun. In his book "On Single Combat" , he already wrote at the time that the comparison is not quite apt. 30 years later, it is still interesting to give some thought to it again. So we suddenly found ourselves considering a number of questions which need to be answered to clarify the matter to our satisfaction.

Two things were clear from the start: it would require research which definitely exceeded the duration of our walk, and I would need to proceed systematically to answer all the relevant questions.

This was an extremely interesting challenge for me, for apart from WingTsun, language and communication have been my private and professional hobbyhorse for almost 30 years. So off to work!

It seemed logical to answer the following questions in sequence:

- How do we learn a new language?

- How do we learn new movements?

- What are the educational concepts in each case?

- Where do the differences lie?

- What common factors or analogies are there?

If I could arrive at the answers, it would be possible to extend SiFu's comparison in a structured way and even make it applicable to further teaching programmes in the EWTO.

How do we learn a new language?

This is a question which the research area of "language development" seeks to answer as part of various scientific disciplines, e.g. linguistics, development psychology or education.

We need to distinguish between a child intuitively and to an extent unconsciously learning its mother tongue, and learning a foreign language later on. It is the latter that is relevant to our question.

When it comes to learning iWT, it does not appear to me to be like learning a mother tongue, which as you say is unconscious. Now that I am working on Latin again with Natalie, I can see parallels with Latin.

Latin is normally taught as a dead language. The teaching method is dissection, analysis, grammatical exercises and translation. One has the (deceptive) feeling that Latin is an artificial language. When learning it, one needs to be totally concentrated and conscious.

In 1970 I passed my advanced Latin examinations and studied Latin and other subjects in Kiel. It was only in 2016 that I discovered a Danish natural learning method by which one can learn Latin like a living language, like one's 1st language – i.e. without translation, analysis etc. – simply by speaking.

If we also want to do this in iWT, the medium must be physical contact with the master, i.e. direct transfer from hand to hand, from arm to arm. To do this, the master must master the art of transferral so as to guide the student. Prof. Tiwald, the great educationalist, once wrote a text about this for me which I now find most useful.

If one does not have such a real master available all the time – the best case would be a brother or father – it is necessary to recognise and practice the laws governing intelligent and effortless movement.

Somebody who learns iWT or a classic, inner martial art, which requires a reorganisation of movement patterns, from childhood within a family, i.e. "at play" so to speak, can "do" it, but he does not know on what his skills are based, i.e. he can later only pass it on by "laying on hands". Because for him, having acquired this inner art as a "mother tongue", this way of moving is "normal" and he cannot understand that not everybody moves in this way.

It comes as no surprise that learning foreign languages is a separate area of research. This discipline concerns itself with a wide range of different factors considered to be essential for learning a foreign language. Here too, there are various scientific areas involved such as cultural anthropology, education science, semiotics or the media sciences.

Looking at the methodological history of foreign language teaching, one thing is clear: it is complex!

Distinctions are made between inductive and deductive methods, and between approaches such as the "grammatical translation method" and the "audiovisual", "transferral" or "communicative" method. The concept of "learning by teaching" is also not without interest.

"Learning by teaching" is a superb self-learning method, especially for iWT: it obliges one to formulate the rules out loud all the time, and to question them.

It is not possible to find a clear and simple answer representing the "latest research findings".

Conclusion: there is a wealth of very different theories and approaches which partly contradict, overlap or supplement each other.

As it was not the purpose of our initial question to write a dissertation about the methodology of foreign language learning, I turned to the next question.

How do we learn new movements?

Which makes our problem even bigger, because in iWT it is not a matter of "different movements" but of "moving differently", for example using different muscles than before for certain tasks.

When the Chinese refer to such a way of moving as "natural", although we have to laboriously understand and learn it, we almost feel we are being made fun of. But what is meant by "natural" is not what everybody does from birth, but instead how one should move according to the unwritten rules of human nature if one wants to achieve the greatest effect with the least effort.

Movement science concerns itself with studying the movements of living beings, especially humans. It is a sub-discipline of various other sciences, e.g. sports science, psychology or education. Four mainstream approaches have become established in movement science: the biomechanical, comprehensive, functional and capability- oriented approach.

Moreover, movement science has in turn given rise to a number of sub- disciplines, e.g. functional anatomy, biomechanics or movement learning.

The latter researches into the learning of movement sequences in e.g. sport, and also into improving this by physiotherapy. It examines the functions and basic biological factors, and also develops different models aimed at explaining the learning of movement using accepted learning theories such as behaviourism, control theory or the theory of information processing.

Here too, the complexity of these different research approaches and results is truly mind-boggling. They build on each other, confirm and contradict each other, lead us forward and back again. Even acknowledged experts must find it hard to keep an overview.

The result of these many (non-) findings was of course inevitable: things did not get any easier when it came to teaching.

What are the educational concepts in each case?

The question of educational concepts in turn opens up an enormous repository of accumulated knowledge, like some gigantic library in which the research results of generations of scientists are stored and catalogued. The terms used range from education theory and critical/constructive didactics to learning theory, information theory and cybernetic or constructivist didactics. And that is by no means all, as each of them contain interesting ideas and approaches.

Be that as it may, you will not find the ONE that explains everything once and for all. At least I was unable to, after many hours of literary research.

After a few days of intensive study I had still not adequately answered any of the questions I put to myself. Although the approach I envisaged looked so logical and promising at first sight, I had to realise that I was getting nowhere.

So I decided to start from the beginning again.

I took SiFu's "On Single Combat" off the shelf again, and read his original words in "How to learn WT?". I also looked to see when he wrote them – the first German edition appeared in 1987.

Every text must be seen in its historical context if one wants to assess it. I therefore referred to SiFu's more recent books to look for any notes or cross-references to this 30 year-old analogy. In the process I noticed a passage in the "Course Book – Inner WingTsun": "Sequence of the architecture in WT". Here SiFu sketches what he already explained in detail in "Fightlogic". Based on the Clausewitzian method of strategic planning, he constructed the concept for a goal-oriented WT teaching method. In this the purpose determines the goals, the goals the strategy, the strategy the tactics and the tactics the movement employed. From this SiFu finally developed the "Big 7 capabilities", so that after over 55 years of research into Inner WingTsun, everything was concentrated on pure function.

Correct, but not the "function" in the usual sense of "purpose", but rather in the sense used by Frege, which Horst Tiwald commended to me and which I explain in the "Course Book".

So now the circle was complete, and I was at last able to extend the old analogy between learning a language and learning WT so that – as initially planned – it even becomes usable for other teaching programmes in the EWTO.

There can be no doubt that both in linguistics and in the science of fighting (combatology), the state of the art (= knowledge accumulated over decades and centuries) achieves the best results of all time in terms of their respective purposes.

The purpose of learning in WT is primarily self-defence. Just as that of learning a new language is communication. Over the decades, there have been numerous theories, concepts, methods and exercises that have entered the curriculum of the EWTO and follow this purpose. Just as countless ideas and approaches have come together in linguistics. In both areas they all have their justification "so long as the function shines out", as SiFu emphasises in his "Course Book".

Though I have to comment that the "purpose" for which something is invented does not have to stay the main purpose. The blue tablets that everybody knows but nobody uses were e.g. originally intended to combat angina pectoris; Zen (or Chan) was developed as a teaching to promote mindfulness, and then helped the Japanese Samurai and Chinese KungFu fighters to be cold-blooded and fearless in combat.

The original purpose of the inner martial art that Boddhidarma (Ta Mo) brought to the Shaolin monastery was not to teach the monks to fight, it was to "keep them awake" during their meditation, i.e. give them energy.

In a similar way, certain Chinese teachings promoting mindfulness use combat to test whether the student can still remain "conscious" in the stress of a fight. In this case combat is just a means to an end. Nonetheless it makes sense to learn just such an art, as it ideally prepares one for a self-defence situation.

In iWT and in On Single Combat, the similarity between language, dialogue and fighting is "close at hand", so to speak. Our hands are our tools, and we use them to fight and to teach.

To this extent the development of WT learning methods reflects that in the field of linguistics: complex problems require complex solutions!

GM K. R. Kernspecht

Markus Senft